Empathy, surprises and non-verbal communication – the relationship between the audience and the performers is an integral part of art

The cultural scene is showing signs of revitalisation as the restrictions related to the pandemic are being lifted. The Research Pavilion of the University of the Arts Helsinki (Uniarts Helsinki) presents works by artist-researchers who examine empathy and power relations that emerge between the audience and the performers in a shared space.

In the nineteenth century, American newspapers started to write about “hobo signs”. These signs were drawn by homeless vagrants in the places they visited, and they were intended as warnings to other vagrants about the dangers presented by hostile landowners and their dogs, or as information about friendly people who might give them shelter.

There is no consensus about whether these signs were in common use among the hoboes, but apparently there were at least some local, marginalised groups of vagrants who used them for communication.

Artist-researcher Jaakko Ruuska makes use of hobo signs in his performance, which takes place in Helsinki on 20 June. Disconnected Space investigates physicality and interaction, things that needed to find new forms of expression during the pandemic. The participants of the performance walk down the streets of the Töölö district, taking notes of their route along the way. During stops, they will write texts and leave them for the other participants to read. The success of this exercise will be evaluated in an event at the conclusion of the performance. This concluding event is also open for public.

“I wanted to examine the experience of how you can attain a shared space when you’re not allowed to be in the same physical location. The performance seeks to find new ways of writing that could lead to an embodied experience of a shared space,” says Ruuska.

The performance investigates themes that are highly topical, and it is organised as part of Uniarts Helsinki’s Research Pavilion in Hietaniemi. Over the summer, the Hietsu Pavilion in Helsinki will host exhibitions, performances, and discussion events that are not only intended to introduce artistic research to the public but are also part of the research carried out by the artists.

Space and presence create empathy

Jaakko Ruuska’s practice focuses on performance and film art. In his doctoral research, Ruuska investigates human interactions and “disconnects” that may disrupt them. The pandemic is a significant kind of disconnect, and it has prevented people from coming into contact with each other, while also inhibiting interactions between art, artists, and the audience. The experience provided by a streamed performance on a computer screen may pale in comparison to a live performance.

According to Ruuska, the physical space and contact between people results in an experience of empathy. He talks about an “empathy disconnect” when this contact is impeded.

Ruuska, who has a degree in filmmaking, does not think that it is necessary to occupy a shared space to enjoy a great experience. Nevertheless, there are ways that filmmakers employ in order to evoke strong feelings of empathy in the film’s audience. Every scene and every image seen on the screen has been cropped, and things are either shared with the audience or intentionally omitted. Successive images can be used to place different things in parallel or to create continuity between the scenes.

It is often cumbersome to organise a remote transmission of a performance that has been intended to be realised in a single space. There are fewer opportunities for cropping or creating parallels, for example, and it is much harder to control the direction of the audience’s experience.

“I’m not saying that streaming altogether prevents feelings of empathy from emerging, but it’s much more restrictive.”

Ruuska has realised the extent to which time, space, and location affect our experiences. In a previous part of his doctoral research, Ruuska made a video work of a route in Kuusankoski that was used to take people to their place of execution during the Finnish Civil War.

Ruuska’s work was shown to the public exactly one hundred years after the events portrayed in the film had taken place. The film brought things to light which had been intentionally erased from public memory. The obscuring of people’s experiences with time and space had resulted in an empathy disconnect.

“Family members were not allowed to visit the place of execution. They were forbidden from bringing any objects to the memorial. The route taken by the condemned was not public knowledge, and there was no clear path visible in the location. The events had obviously been forgotten,” says Ruuska.

A musician controlled by a machine and the audience

Pianist and composer Libero Mureddu is also interested in the relationship between art and the audience. In his experimental musical performances that are part of his doctoral research, the audience can give orders to the musicians of the Septad Ensemble led by Mureddu.

The audience will enter their instructions to the musicians through a website, after which they will be automatically transmitted to the performers’ iPads. The first show included in the Joy Against the Machine concert series was performed in February, and in that performance the musicians were instructed by an AI software instead of people. The instructions given by the software pertained both to the music and to its interpretation: Jump! Be a cat! Play major triads! Think about your mother!

Mureddu is an expert in improvisation, and in his research, he investigates the tacit knowledge possessed by the improvising musician. He is also interested in power relations: what does it feel like to take orders from a machine or a person? In the earlier show, the performers found it surprisingly easy to follow the orders given by the machine; in fact, it did not feel like taking orders at all. When you follow orders given by a machine, you retain a sense of autonomy.

“Of course, it’s also dangerous. I need to study this further, but my assumption is that we can follow orders if we don’t feel or see the human who dictates what we do.”

It may be that giving power to the audience will serve as a reminder to all music listeners during the pandemic that art is interaction – not just the consumption of ready-made cultural products. For Mureddu, artistic research, such as free improvisation, also includes an element of risk-taking in front of an audience. He wants to be surprised and hopes that the audience will also surprise him.

“I want to enter into a moment where I really don’t know what’s going to happen, because that’s when the real improvisation comes.”

The energy of the audience is transmitted to the musicians

Whenever a show is performed remotely, the audience’s experience of it will be affected. A remote performance will also cause changes to the show itself as well as to the way the performers experience it.

Mureddu takes a positive approach to the possibilities afforded by technology. Nevertheless, it is also true that improvisation is essentially created through communication at a specific moment in time. A professional will let the performance lead the way to an unanticipated result.

“In the performance, things come and go. When a performance is streamed and you know the recording will stay, it creates a certain pressure for improvisation. You want the recording to be flawless.”

When Mureddu performed in the concert conducted by the machine, the audience occasionally laughed at the orders given by the computer. Having people watch the show in the first place is enough to affect the musical performance.

This is what we have been craving for during the pandemic. Both the artists and the audience have surely missed the interaction that takes place during the performance.

“I think there is some kind of transfer of thought energy in it. I don’t want to sound too spiritual: it’s just something I can’t verbalise,” says Mureddu.

We may come out of the pandemic with a better awareness of the social significance of art. When Jaakko Ruuska visited his colleague’s exhibition after a long break and had a conversation with the artist, he could feel the anxiety caused by the pandemic subside.

“Perhaps the social dimension of art can now be recognised more clearly: the fact that when you look at art, you’re looking at something that someone wants you to see. Someone has produced the artwork to bring an observation into tangible form. If they hadn’t done so, the observation would remain forever private.”

Libero Mureddu’s next concert is on the 4 September at the Helsinki Music centre in Feel Helsinki event. The audience can send orders beforehand and the computer programme will randomly pick them one at the time during the performance.

Factsheet

What is the Research Pavilion?

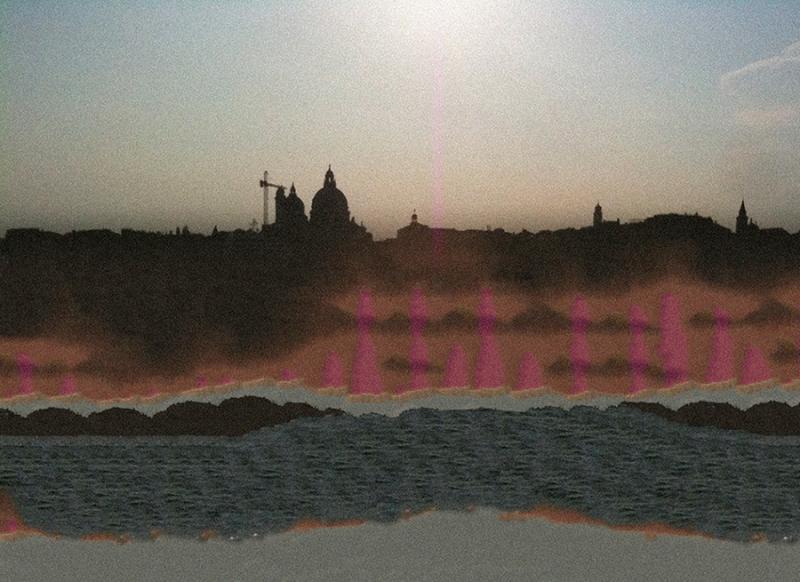

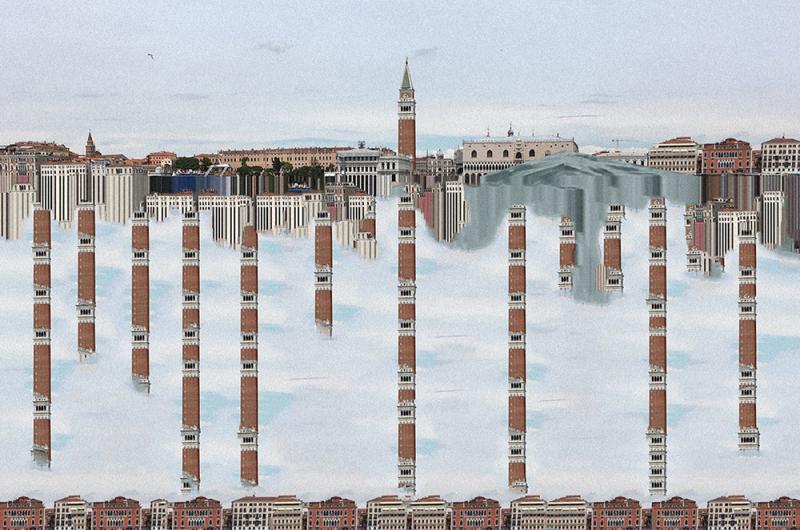

- The Research Pavilion is a continuing project coordinated by Uniarts Helsinki, which introduces research as part of important contemporary art events. It was organised in connection with the Venice Biennale in 2015, 2017, and 2021. In the summer of 2021, the Research Pavilion will come to Helsinki 5 June – 29 August. It will be organised at the Hietsu Pavilion.

- The performances, exhibitions and discussions at the Hietsu Pavilion shed light on topics that are somehow situated in the fringes or in the margins; things that we may not recognise or which we need to examine from a new perspective. The event includes works by artists whose practice includes an element of research.

- Disconnected space by Jaakko Ruuska is a research event in the form of a playful, participatory performance, that studies the possibility for intercorporality in the pandemic situation.

- Browse all Research Pavilion events here.