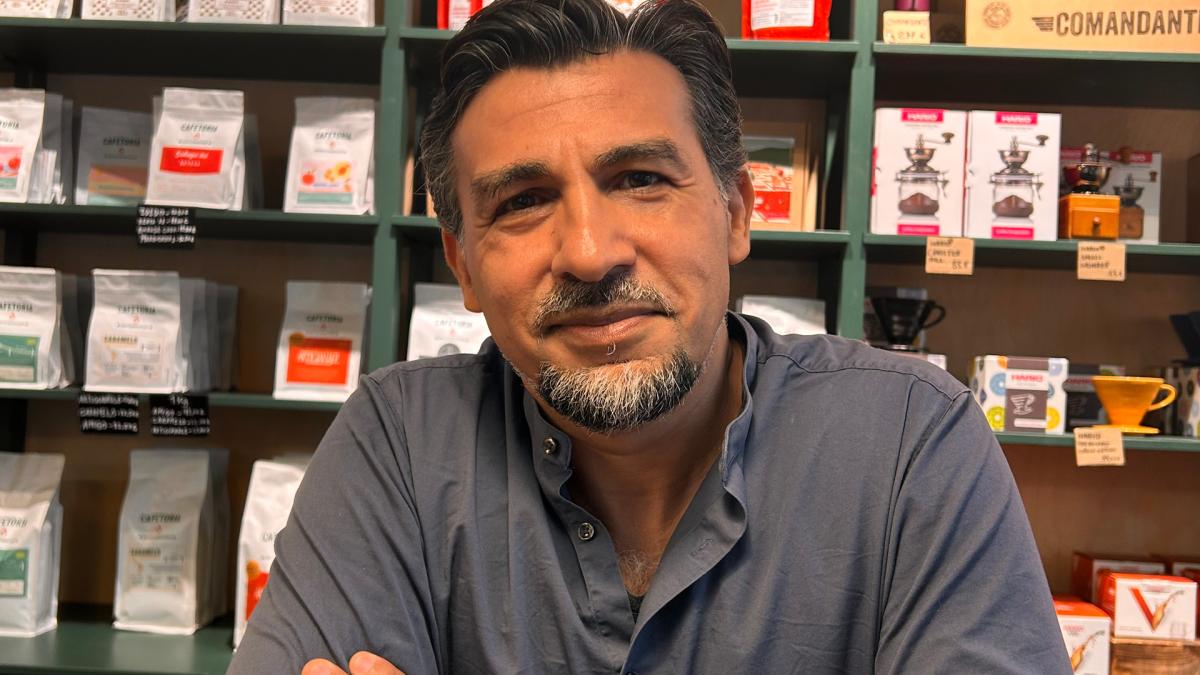

Nitin Sawhney: “AI is just a tool – what’s important is to focus on what we actually want to achieve”

Our visiting researcher Nitin Sawhney has combined science and technology, human rights and artistic research in his career. In December 2025, Uniarts Helsinki awarded him the title of docent, which is a recognition awarded for significant research or artistic merits.

In the early morning hours of 13 June, Israel carried out multiple strikes on Iranian nuclear and military sites. Earlier that week, Nitin Sawhney’s father had passed away, and he had flown from Finland to New Delhi, India, to be with his family.

“The pain of losing my father was mixed with the pain of the bombings in my childhood homeland.”

Born in New Delhi, Nitin Sawhney spent his childhood in Tehran, Iran, where his father worked as a civil engineer in the 1970s. In 1979, Iran underwent a revolution that transformed it from a monarchy to an Islamic theocracy. Nitin’s family moved to Bahrain, while he briefly attended a British era boarding school in the Himalayas.

“The area of present-day Iran is one of our oldest civilizations. Iran is a politically complex and culturally valuable country that has contributed a great deal to the world. It breaks my heart to see how it has been treated by Western powers over the years, but also how its own oppressive regime continues to restrict the freedom and aspirations of Iranians living there.”

Sawhney also has a wealth of experience in another area that is, in a very sad way, quite topical. He has worked on participatory media and filmmaking in refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

“The Middle East is very misunderstood, especially in the West,” he says.

The history of the region is complex.

“The conflict is only partly ethnic; it is largely a regional conflict with roots in colonialism,” he says.

Artistic engagement conveys the complex history of the Middle East

In the 2000s, Sawhney was a PhD student at one of the world’s top universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Already back then, a surge in violence and human rights violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) urged him to co-organise public seminars and protests at MIT. As a young researcher, Sawhney felt conflicted and wondered what role artists, scientists and scholars should play in a conflicted world.

“It wasn’t until I began engaging in activism in a U.S. college campus that I realised that I had an undeniable cultural and political connection to the Middle East from growing up there.”

MIT also fostered an open and free exchange of political thinking led by many eminent professors like Noam Chomsky whom Sawhney briefly interacted and organised seminars with. Sawhney realised that academic discourse and activism alone would not be enough to improve our understanding of conflict and social justice.

“Art, media and culture are really central to making us aware of the complex history of the Middle East.”

In 2006, Sawhney founded Voices Beyond Walls, a non-profit initiative that organised workshops to teach digital storytelling and foster participatory media among children with community centres in Palestinian refugee camps.

“I invited local and international artists and educators each year to co-teach workshops and work closely with young people in the refugee camps to nurture narrative and artistic thinking with participatory methods. We worked with Palestinian youth so that they could use tools like urban mapping, photography, theatre and filmmaking to reimagine their dreams, struggles and aspirations.”

This led to Sawhney co-founding and co-organising the annual Boston Palestine Film Festival since 2007 to engage mainstream audiences with Palestinian media narratives. Dozens of documentary, fiction and experimental films by Palestinian and international filmmakers have been screened at the festival each year, which has now emerged as one of the largest Palestinian film festivals worldwide.

“Our goal was to humanise the plight of a misunderstood people to American audiences through cultural and cinematic narratives about their lives.”

While working in Gaza in 2010–2013, Sawhney and filmmaker Roger Hill co-directed the feature-length documentary film Flying Paper (2014), which showcases the playful culture of kite making and flying among young children in Gaza and their quest to break the Guinness World Record for the most kites ever flown.

While teaching at the MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT), Sawhney recognised the role of artistic intervention, film and performance as modes of critically engaging human rights violations and injustice in other global contexts.

After joining the New School as an assistant professor of media studies, Sawhney began working with artists, curators and community activists in Guatemala organising workshops, exhibitions and a performance-based documentary film project called Zona Intervenida. During the Guatemalan Civil War (1960–1996), an estimated 200,000 Guatemalans, 83% of whom are indigenous Mayan people, were killed en masse mostly by government forces supported by the United States. Few Americans knew what role their government played in such conflicts, were it not for documentary films like “When the Mountains Tremble” by award-winning filmmaker Pamela Yates and compelling narrative accounts by brave Guatemalan artists, writers and journalists over the years.

Sawhney has focused on themes of creative resistance and historical memory in conflict situations in both regions, which he feels has been transformative for his research, teaching and artistic practice. Politics is inevitably an integral part of his work.

“Every course that I teach is inherently political, and I can’t imagine teaching without critically examining the underlying politics. It’s simply a result of my lived experiences.”

The goal is responsible and inclusive artificial intelligence

Unsurprisingly Sawhney’s participatory and artistic work in societal contexts affected how he conducted academic research on machine learning, human-centred design and co-creative learning.

Sawhney’s ethos of engaging critically in inclusive, trustworthy and responsible artificial intelligence (AI) sounds worthwhile, but how does he see the rapid development of AI at the moment?

“At MIT, I was already using machine learning, although it wasn’t yet its own, separate field. That’s why AI has always been just one tool among others for me to explore computational media or use data for artistic expression.”

As a professor of practice at Aalto University’s Department of Computer Science, Sawhney was involved in a project that used machine learning to understand disinformation in the media. The research, supported by the Research Council of Finland, revealed how various parties and social media bots with malicious agendas shaped public health discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially on Twitter.

He also led a multidisciplinary project funded by the Kone Foundation and the Research Council of Finland that investigated algorithmic tools and practices for designing public sector services in Helsinki and Espoo. The team identified both risks and opportunities for human-centred public AI services, especially among vulnerable communities like migrants.

“I’m interested in how we’re able to address social injustice, ecological crises or conflicts. Our toolbox needs interdisciplinary research that combines social science, design, artistic practices, law and technological tools like AI. That’s the sort of culture I tried to foster in my research group at Aalto University.”

Sawhney believes it is more important to focus on how we understand and tackle complex societal conditions, rather than the tools or technologies we develop and deploy.

“I’m not so much interested in AI itself, but rather in nurturing new possibilities between humans and machines.”

He believes cooperative human-AI learning and expression offer more interesting possibilities for research, citing examples he has worked on such as use of AI as a co-creative partner in music and sound composition, or supporting human counselling services as a knowledgeable partner.

“When it comes to using and developing generative AI systems, we should be much more cognizant of their limitations and be able to better understand and influence their emerging outcomes. If AI reduces our agency or critical thinking, which is what a recent MIT study of ChatGPT use by young students found, then we are heading in the wrong direction.”

Sawhney believes that the uncritical use of large language models (LLMs) entails worrying features. He lists problems such as bias, disinformation, privacy and copyright infringement, as well as the ecological impact, but also how such AI data infrastructures controlled by a handful of big tech companies diminishes the democratic agency and oversight of civil society.

“I notice that even my colleagues use them without questioning it. I don’t use commercial LLMs or chatbots in my research, teaching or personal work.”

Sawhney’s research team has examined the use of Knowledge Graphs (KGs) as an alternative way to complement LLMs to provide more trustworthy and explainable outcomes. They organise data as a network-like structure, simultaneously emphasising meanings and relationships of things.

Artificial intelligence in warfare

Sawhney has become increasingly concerned with the role of AI in technologised warfare and human rights violations. Over the past year he organised interdisciplinary symposia (Contestations.AI) and international workshops to draw critical perspectives from researchers, journalists, social scientists, filmmakers and artists.

While at Uniarts Helsinki, Sawhney has begun conceptualising a documentary film, titled “Where’s Daddy?”, that examines the role of artificial intelligence in conflicts and warfare, and how it dehumanises people’s lives affected by war.

“The concept for the film is both personal and research-based, and also partly fictional. We often talk about the impact of war on women and children, but in this film, I want to delve into the experiences of fathers and sons (whether as combatants or civilians) who often become the dispensable inhumane toll of warfare.”

The film will examine how the use of AI-based systems, like Lavender, Gospel and Where’s Daddy used in Gaza, amplify the speed and scale of human casualties in technologised warfare and obscure the human narratives of injustice, loss and survival.

Sawhney’s intellectual identity has been shaped by an unconventional trajectory from science and technology to media arts and cultural studies while engaging with conflict and social justice.

“As ‘public intellectuals’, we all as researchers, teachers, students and scholars have a responsibility to speak up and probe the complexities of conflict and injustice through transdisciplinary research, creative expression and societal engagement,” he says.

Nitin Sawhney

- Docent at the Uniarts Helsinki Research Institute

- Before Uniarts Helsinki, worked as professor of practice at Aalto University, assistant professor of media studies at The New School, and lecturer at the MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT)

- Completed his PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2003, while conducting research at the MIT Media Laboratory

- Co-founded and worked with technology start-ups in Cambridge and New York City

- Directed award-winning documentaries in Gaza and Guatemala